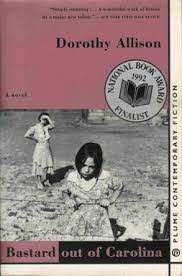

Cover photo of my version

has a Dorthea Lange photo

The 1992 National Book Award for fiction went to Cormac McCarthy for his modern-day Western, All the Pretty Horses..

One of the finalists for that year’s prize was Dorothy Allison gritty Bastard Out of Carolina, a book that’s been sitting on the shelf of one of my bookcases for, well, decades. Not even sure when or where I bought it. Or why. I must have read a review.

Finally got around to reading it last week, and I really delayed my reading pleasure by 20-30 years. Gritty, sad, hopeful – just a snapshot of the human condition by a poor white extended family in a small 1950’s North Carolina mill town.

Narrated by the titular character – Ruth Anne, AKA Bone – from the time before her birth until she’s roughly 13 years old. It doest even seem hokey that she narrates the terms of her gestation (briefly) and birth – the way it’s written indicates that her family has a strong oral tradition, and she’s just passing on what she’s heard from her relatives, colored by her own experiences.

The men are the main breadwinners – this is the 1950s in the South – but they are almost all damaged goods and get relatively little play in the book. Feared by townspeople for their tempers, they are drunks, self-indulgent and philanderers. They protect their families as needed, but that was not their focus.

It’s the women who hold the families together – each is a vertebrae that form the spine that supports the entire group. And that even includes a young Bone, who is sent to a dying aunt’s house to help the cancer-stricken woman until her help is no longer needed. The female children spend a lot of time at different aunts’ houses – again, it’s the women who are the glue. Sometimes it’s the aunt helping the child, sometimes it’s the other way around.

The main theme of the novel is the intrinsically unbreakable bond between mothers and their children, but also of the women and all their female relatives. The men and boys will endure.

Without airing any spoilers, when this primary bond slips even just a little near the end of the book, it upends Bone’s entire world.

The book’s epigraph is a James Baldwin quotation and it really sets the mood:

People pay for what they do, and still more, for what they have let themselves become. And they pay for it simply: by the lives they lead.

– James Baldwin

This novel reminded me of Jane Hamilton’s The Book of Ruth, about a different white trash family – this time in Wisconsin – and the (quite different) relationship between the daughter, Ruth, and her mother.

Neither is a feel-good novel, but both are well written and pack a punch.